Introduction

During the last few decades, it has become evident that we can no longer think of socio-economic development in isolation from the environment. The nature of issues confronting us along with an increasing interdependence among nations necessitates that countries come together to chart a sustainable course of development. The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), held in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992, was a milestone event, effectively focussing the world's attention on environmental and development problems we face as a global community. The Summit brought together governments from around the globe, representatives from international agencies and non-governmental organizations with the objective of preparing the world for attaining the long-term goals of sustainable development.

Agenda 21 adopted at the conference, represents a global consensus and political commitment at the highest level on socio-economic development and environmental cooperation [1]. The foremost responsibility for leading this change was placed on national governments. Each government was expected to design national strategies, plans, and policies for sustainable development — a national Agenda 21 — in consonance with the country’s particular situation, capacity and priorities. This was to be done in partnership with international organizations, business, regional, state and local governments, non-government organizations and citizens groups. The Agenda also recognized the need for new assistance for developing countries to support the incremental cost of actions to deal with global environmental problems, and to accelerate sustainable development.

Since UNCED, extensive efforts have been made by governments and international organizations to integrate environmental, economic and social objectives into decision-making through new policies and strategies for sustainable development or by adapting existing policies and plans. As a nation deeply committed to enhancing the quality of life of its people, and actively involved with the international coalition towards sustainable development, the Summit provided India an opportunity to recommit itself to the developmental principles that have long guided the nation. These principles are embedded in the planning process of the country and therefore the need for a distinct national strategy for sustainable development was not felt. As we approach Rio +10 and set new milestones based on an evaluation of past performance, this exercise attempts a critical appraisal of national and sectoral planning in India and how it has sought to address sustainability concerns since and even prior to Rio. The objective of this review is to evolve strategies for the sustainable development for the country.

To put the analysis that follows in perspective, it will be in order to sketch a brief profile of the country.

India: a profile

India is the seventh largest country in the world and Asia’s second largest nation with an area of 3.29 million square kilometres. The Indian mainland stretches from 8o 4 to 37 o 6 N and 68 o 7 to 97 o 25 E. The country is set apart from the rest of Asia by the Himalayas to the north, and is flanked by the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Arabian Sea to the west, and the Indian Ocean to the south. India is characterized by variable terrain, starting from the Himalayas to flat rolling plains along the Ganges deserts in the west and an upland plain (the Deccan Plateau) in the country’s south. India has numerous perennial and seasonal rivers, a rich variety of soils and a great diversity of natural ecosystems. There are also diverse climatic zones varying from tropical monsoon in the south to temperate in the north.

Natural resource endowment

Minerals and energy resources

India is richly endowed with mineral resources, which include fossil fuels, ferrous and non-ferrous ores, and industrial minerals. There are about

20 000 known mineral deposits in the country and as many as 87 minerals (4 fuels, 11 metallic, 50 non-metallic, 22 minor minerals) are being exploited (TERI, 2001b). The country has abundant reserves of bauxite, coal, dolomite, iron ore, manganese, limestone, magnesite and adequate reserves of chromite, graphite, lignite, and rock salt. The production of some important minerals over the years is given in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Mineral production (in million tonnes)

|

Mineral |

1970 |

1990 |

1998-99 |

|

Iron ore |

16.6 |

55.6 |

70.7 |

|

Bauxite |

1.4 |

5.0 |

6.4 |

|

Limestone |

23.8 |

70.1 |

106.8 |

Source. Ghosh and Dhar (2000) cited in TERI (2001b)

Coal remains the single most important source of energy in India with a reserve-production ratio of over 200 years (Table 1.2). The Geological Survey of India has estimated India’s proven coal reserves to be approximately 8% of the world’s total proven reserves (TERI, 2001a).

Besides conventional sources, the country is richly endowed with non-conventional energy resources such as solar, hydro and wind. The country stands out as being the only one in the world with a separate Ministry of Non-conventional Energy Sources. India’s renewable energy programme is one of the largest and most extensive in the world. Currently, almost 3% of India’s installed power capacity comes from non-conventional energy sources.

Table 1.2 Proven reserves of fossil fuels and reserve-production ratios

|

End 1991 |

End 2000 |

|||||||

|

Reserves |

R/P |

Reserves |

R/P |

|||||

|

Fuel |

India |

World |

India |

World |

India |

World |

India |

World |

|

Coal (billion tonnes) |

62.54 |

1040.52 |

195.00 |

239.00 |

74.73 |

984.21 |

223 |

227 |

|

Crude oil (billion tonnes) |

0.80 |

135.40 |

25.60 |

43.40 |

0.6 |

142.1 |

17.3 |

39.9 |

|

Natural gas (trillion cubic metres) |

0.70 |

124.00 |

48.80 |

58.70 |

0.65 |

150.19 |

24.8 |

61.0 |

Source. BPSR (2001), TERI (2001a)

Forests and biodiversity

A large variety of forests is found in India ranging from evergreen tropical rain forests in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Western Ghats and the North-Eastern states to dry alpine scrub in the Himalayan region. Between the two extremes the country has semi-evergreen rain forests, deciduous monsoon forests, thorn forests, subtropical pine forests and temperate forests. The forests of India have been divided into 16 major groups comprising 221 types. The forest cover of the country, as per the assessment by Forest Survey of India, is 63.73 million ha constituting 19.39% of the geographic area of the country out of which 37.74 million ha (11.48%) is dense forest (crown density more than 40%), 25.50 million ha (7.76%) open forest (crown density 10%-40%)

and 0.49 million ha (0.15%), mangroves (FSI, 2000). Over 45,000 plant species are found in the country. Several thousand of them are unique to the country. Two international biodiversity hotspots have been identified in the Eastern Himalayan region and the Western Ghats.Fresh water

India is considered rich in terms of annual rainfall and total water resources available at the national level. The average annual rainfall, equivalent to about 4000 billion cubic metres (BCM), however, is very unevenly distributed both spatially as well as temporally. This causes severe regional and temporal shortages. Utilizable resource availability in the country varies considerably from 18,417 cubic metres in the Brahmaputra valley to as low as 180 cu m in the Sabarmati basin (Chitale, 1992). Precipitation varies from 100 mm a year in western Rajasthan to over 9000 mm a year in the north-eastern state of Meghalaya (Engleman and Roy, 1993). With 75% of the rain falling in the four monsoon months and the other 1 000 BCM spread over the remaining eight months, Indian rivers carry 90% of the water between June and November, making only 10% of the river flow available during the other six months.

Governance structures

India, at the time of its Independence faced many challenges. The partition of the country produced severe communal stress. There were a large number of small states ruled by dynastic monarchies. Assimilating these into the mainstream of the Indian Union was an uphill task. The country required a strong governance structure to ensure peace and rapid socio economic development. The fundamental principles of governance that were enunciated then were democracy, equality and the rule of law. These principles have, over the last fifty years and more, taken deep roots and the country has had an unbroken democratic continuum.

The basic democratic character of the Indian state has, since Independence, become stronger, wider and deeper. The country has a strong and vibrant legislature with an independent judiciary, that have acted as a balance to the executive. The planning process in the country is so structured as to ensure a iterative mechanism of planning based on the interaction between the centre, states and local bodies. At the national level, the Planning Commission draws up Five-Year Plans in consultation with various ministries and state governments, reflecting the nation’s priorities. The Five-Year Plans are divided into annual plans, which set the prioritized and short-term developmental goals. The performance of programmes is regularly monitored, by a mid-term review of the Plan. The implementation of developmental programmes in the country is carried out through adecentralised and broad-based governance machinery. The country has a fairly uniform pattern of devolution of responsibility between the centre and the states and between the states and the local bodies. There is an active and independent press and since the 90’s an equally effective electronic media. A large number of NGO’s are active and help to support the formal governance structure. Increasingly, information technology is playing an important role in bringing about greater awareness, peoples’ participation and transparency. These features of the Indian system of governance are elaborated upon in the following sections.

Legislature and Judiciary

The Indian state is characterised by the classical division of powers between the executive, legislature and judiciary. The principles governing this division are laid out in the Constitution. Amendments have been made in the Constitution from time to time to meet the changing needs and to cope with unforeseen situations. The state is federal with 28 states while seven smaller administrative units are directly controlled by the centre (Union Territories). Elections to the legislature, both at the centre and the states, are supervised by an independent Election Commission, whose independence is safeguarded by constitutional provisions. Elections in India are the largest in the world and have been accepted as being fair with provisions for correction in case of any aberrations. The legislatures have the powers to approve/reject/modify all legislation, review financial allocations, expenditures, revenue collection and the overall performance of government. Proceedings of the legislatures are open. Important proceedings of the Parliament are also televised live to a national audience.

The Judiciary also has a federal character with the Supreme Court at the apex, High Courts in the states and other courts below the high courts in the states. The Judiciary is independent and has acted as an effective check on both the executive and the legislatures. In the recent past the Judiciary has also played a pro-active role in upholding the rights of the citizens particularly through the route of Public Interest Litigation. In the area of environment, in particular, the courts have been active in achieving a greater degree of compliance with the laws and in upholding the right of the citizens to acceptable quality of water and air.

The other positive feature of the State is that it has been continuously ruled by elected civilians. The large armed force of the country has protected the country borders from external aggression and plays an important role in countering terrorism in some of the border states as also assisting the civilian administration to cope with internal disturbances and natural calamities.

Devolution to states

The Constitution lays down the division of powers and responsibilities between the centre and the states. These have provided the basis for an enduring federal structure. Broadly, issues requiring a national perspective like defence , external affairs are with the centre. In the areas of social and economic issues there is shared responsibility. Often the centre takes the initiative on important issues and involves the states in the implementation. Thus the "green revolution" in agriculture was a central initiative implemented by the states. Financial flows to the states are guaranteed by leaving certain taxation powers with the states. This is supplemented by the awards of the Finance Commissions, set up every five years under the Constitution – these lay down the principles of revenue sharing of central revenues between the centre and states.

Devolution to local bodies

India has had a long history of local self government, starting well before Independence. After Independence greater use was sought to be made of these bodies in socio- economic development of the country. In 1993 the Constitution was amended to provide constitutional protection to these bodies. This was done in three ways. First there were constitutional safeguards for regular elections and the establishment of State Election Commissions to ensure free and fair elections. Second the powers and functions of these bodies were laid down in the Constitution and it was expected that states would follow this national pattern by amending the state legislation where required. Finally there was a provision for State Finance Commissions (on the lines of the National Finance Commission) that would ensure an adequate level of revenue sharing between the state and the local bodies. This move has provided the basis for greater devolution to elected local bodies and thus to the local communities. The amendment was also an important step towards the empowerment of women and increasing their participation in decision-making since it reserved 33% seats in urban municipalities and the panchayat raj institutions for women.

Education, awareness and the role of media

The rise in the literacy level along with efforts to mainstream the less privileged in the society have strengthened the decentralised governance system in the country. The media has played an important role in awareness generation. The country has an active press that has guarded its freedom zealously. Given the large diversity of the country, regional papers in the local language far outnumber the national press that is dominated by the English press. Of late there has been a veritable explosion of television channels, once again with a very large number of regional channels in the local languages. The media has played an effective role in upholding the basic rights of the people. It has thus acted as yet another forum where people can seek redress of their grievances, where the other forums are not effective. It is also an instantaneous barometer of public opinion on issues that are contentious. With growing literacy, the effectiveness of this medium in moulding public opinion has been growing. It has thus proved to be a valuable instrument to strengthen the basic democratic character of the Indian governance structure.

Transparency and peoples’ participation

There has been a growing trend to provide for greater transparency in the functioning of Government. The natural complement of this process has been the parallel trend of allowing people to participate in decision making at all levels. Important issues are debated and discussed before a decision is taken. Consultations are held, both by Government and by Parliament, with important stakeholders. The Five-Year Plans are also finalised only after consulting experts from various fields and disciplines. Similarly, in the case of environmental clearance all major projects have to go through the process of a public hearing. Again in the case of forests a new style of governance has been introduced in the form of Joint Forest Management where both, the government and the local community, participate in managing the forest resources. Use of independent regulatory commissions is yet another administrative innovation to impart greater transparency and peoples’ participation to the governance structure. The Indian system of governance has thus shown remarkable resilience in adapting to changing situations and learning from the experience of other countries. Throughout this process, the fundamental principles of democracy and openness have not only been retained but also strengthened.

Information technology and e-governance

In this process the new opportunities thrown up by information technology have been made full use of. There is now a mass of information available on the Internet on the performance of the government, important new initiatives and plans for the future. The Internet is also being used for wider consultations – important documents, like the Convergence Bill (which seeks to provide a uniform regulatory structure for the converging telecommunications, entertainment and information technology sectors) are placed on the Internet for comments and feedback. The electronic media is also fostering efficient governance through speedier communications, uniform databases that can be used for multiple departments like ration cards, voter identity cards etc and public services such as tracking the status of rail reservations and passport applications.

Challenges and administrative reforms

Governance is an ongoing process that has to continually adapt to new challenges, situations and the opportunities provided by new technologies. The Indian system, rooted as it is in the fundamental principles of democracy, respect for the rights of individual citizens and openness, has shown ample evidence of its robustness in continuous adaptation to these changes. Administrative reforms have to be seen not as a one time effort but an ongoing process of change, adaptation and improvement. At every level of governance, both within the various organs of the state and the other agencies like the media, NGO’s and local communities, there has been a continuous process of change. This change has led to a progressive improvement in the openness of the system and a greater degree of responsiveness. Given the vast size of the country, the wide differences in traditions and cultures, this is an unmistakable sign of the basic health of the governance structure and its capacity for continuous correction and self improvement.

Economic progress

The country has witnessed sustained growth since Independence; the per capita net national product in constant 1993-94 prices has grown from Rs 3687 (1950-51) to Rs 10 254Q [2] (2000-01). GDP at factor cost has grown from Rs 1404.8 billion (1950-51) to Rs 11939.2 billion (2000-2001) [3]. The sectoral composition of GDP has changed overtime — the share of agriculture has declined, while that of industry and services has increased (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Gross Domestic Product at factor cost by the industry of origin (at 1993-94 prices)

|

GDP at factor cost Rs billion |

Percentage share |

|||||

|

Year |

Agriculture, forestry, logging, fishing, mining and quarrying |

Manufacturing, construction, electricity , gas and water supply |

Trade transport storage and communication |

Banking and insurance, real estate and ownership of dwellings |

Public administration and defence and other services |

|

|

1950-51 |

1404.8 |

59.19 |

13.29 |

11.95 |

6.69 |

9.41 |

|

1970-71 |

2963.0 |

48.12 |

19.91 |

13.73 |

5.94 |

10.69 |

|

1990-91 |

6930.5 |

34.92 |

24.49 |

18.73 |

9.69 |

12.18 |

|

2000-01* |

11939.2 |

26.55 |

24.99 |

22.34 |

12.56 |

13.53 |

*quick estimates

Source. MoF (2002)

The share of agriculture in GDP has come down to 27% from as high as 60% at Independence; however, about two third of India’s workforce still depends on agriculture for its livelihood. The Green Revolution which worked through introduction of high-yielding varieties and large and assured quantities of fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation water helped transform the economy from one deficient in food grains to one that is self-sufficient. The area under food grains accounts for 65% of the total gross cropped area and commercial crops (such as oilseeds) make up 25% (2001). Wheat and rice are grown on nearly two thirds of the area on which food grains are cultivated. About 38% of the total gross cropped area was irrigated in 1997/98. Though around 84% of the country's total water consumption for irrigation 62% of the cropped area is still dependent on the monsoons for water.

The Ninth (1997-2002) and Tenth (2002-2007) Five-Year Plans perceive accelerated agricultural growth as a means of reducing the incidence of poverty and enhancing employment. It is believed that supply side factors — technology, fertilizers, irrigation, infrastructure and credit would be the prime movers for an accelerated and sustainable growth of Indian agriculture (Rao and Gulati, 1999).

The decade of nineties witnessed fundamental reforms that led to the removal of entry barriers, reduction of areas reserved for the public sector, liberalization of the foreign investment policy and import policy for intermediates and capital goods, all contributing to an upsurge in industrial growth. Overall growth in the last decade was marked by cyclical fluctuations with the peak level of industrial growth at 13% in 1995-96. It has slackened thereafter to around 6.5% annually. The EXIM (export-import) Policy for 1992-97 aimed at bringing about major reforms in the trade policy for accelerating India’s transition towards a globally integrated economy. The phasing out of import restrictions, abolition of import quotas, quantitative restrictions, have all played an important role in enhancing trade opportunities. Exports (including re-exports) from the country have increased from US $ 18.2 billion in 1992-93 to US $ 44.5 billion in 2000-01 while imports have gone up from US $ 21.8 billion to US $ 50.53 billion in the period (MoF, 2002).

The service sector grew in the 1990s with its share in GDP rising from 28% in the early 1950s to 41% in 1990-91 and around 49% in 2000-01. Sectors such as software services and IT-enabled services have emerged as new sources of strength, creating confidence in India's competitiveness in the world economy. The Tenth Plan aims at providing further impetus to the rapid growth of these sectors, which are likely to create high quality employment opportunities.

Social development

India's population was estimated at 1 billion as on 11 May, 2000 i.e. 16% of the world population on 2.4% of the globe’s land area. Half a century after formulating the national family welfare programme, India has been successful in reducing the crude birth and total fertility rates, halving the infant mortality rate (IMR), and reducing the crude death rate. The average life expectancy in the country has also increased (Table 1.4).

Table 1.4 Selected health indicators for India

|

Indicators |

1951 |

1998 |

|

Crude Birth Rate (per 1000), (SRS) [4] |

40.8 |

26.4 |

|

Crude Death Rate (per 1000), (SRS) |

25.0 |

9.0 |

|

Infant Mortality Rate (per 1000 live births), (SRS) |

146.0 |

72.0 |

|

Total Fertility Rate, (SRS) |

6.0 |

3.3* |

|

Life Expectancy (years) |

37.0 |

62.0 |

* 1997

Source. MoF (2002), National Population Policy, 2000 Government of India [5].

The country has also made significant progress in reducing poverty (Table 1.5). Between the mid-1970s and 1993/94 the proportion of the

people living below the poverty line (the head count ratio) [6] declined steadily from 55% to 36% and further to 26% in 1999-2000. The incidence of poverty, defined as the percentage of population below a specified poverty line is highest in Orissa (55%), West Bengal (51%), and Himachal Pradesh (45%) and low in Andhra Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, and Kerela (Shariff, 1999).

Table 1.5

Estimates of poverty (%)|

Year |

All India |

Rural |

Urban |

|

1973-74 |

54.9 |

56.4 |

49.0 |

|

1977-78 |

51.3 |

53.1 |

45.2 |

|

1983 |

44.5 |

45.7 |

40.8 |

|

1987-98 |

38.9 |

39.1 |

38.2 |

|

1993-94 |

36 |

37.3 |

32.4 |

|

1999-2000 |

26.1 |

27.1 |

23.6 |

Source. MoF (2002)

Access to reliable and affordable energy services is an important indicator of social development. Despite an increase in the per capita consumption of commercial fuels like electricity, traditional fuels still dominate the household energy profile. Moreover, there is a marked disparity in the levels of energy consumption in the rural and urban areas of the country (Table 1.6).

Table 1.6

Monthly per capita consumption — All India|

All India |

Rural |

Urban |

||

|

1987-1988 |

1999-2000 |

1987-1988 |

1999-2000 |

|

|

Fuel wood and chips (kg) |

16.24 |

17.70 |

7.40 |

5.34 |

|

Electricity (kWh) |

1.30 |

4.54 |

7.18 |

20.89 |

|

Kerosene (lt) |

0.57 |

0.57 |

1.29 |

.71 |

|

Liquefied petroleum gas (kg) |

0.01 |

0.14 |

0.39 |

1.31 |

Source. TERI (2001a ), NSSO (2001)

Drinking water and sanitation facilities are basic requirements for healthy living. There has been significant progress in improving these services (Table 1.7), but there are marked rural-urban and regional inequalities in the country. While in some states such as Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Pondicherry and Chandigarh, 100% access to water supply services in rural areas has been achieved, in others such as Assam, Punjab and Kerela the percentage habitation fully covered is only 57.4%, 33.3% and 22.2% respectively (MoRD, 1999). Coupled with this are inadequate resources for treating wastewater. Improvement of water supply and sanitation facilities are both priorities of the government.

Table 1.7 Population covered with drinking water and sanitation facilities (%)

|

Area |

1985 |

1990 |

1999 |

|

Drinking water supply |

|||

|

Rural |

56.3 |

73.9 |

98.0* |

|

Urban |

72.9 |

83.8 |

90.2@ |

|

Sanitation facilities |

|||

|

Rural |

0.7 |

2.4 |

9.0* |

|

Urban |

28.4 |

45.9 |

49.3@ |

*With Government initiative only under CRSP, MNP, JRJ, and IAY, coverage through private initiative is not known

@As on 31-3-1997

Note:

Percentage coverage in respect of rural water supply and sanitation are based on population covered in current year to corresponding 1991 census population

Percentage coverage in respect of urban water supply and sanitation are based on population covered in current year to corresponding current population

Source. MoF (2001)

Improvement in the health status of the population has been one of the major thrust areas in the social development programmes of the country. Over the years there has been a significant improvement in health standards particularly among the poor. Access to basic health facilities has improved and many dangerous diseases have been eradicated. This has been achieved through technological breakthroughs and improvements in the access to health, family welfare and nutrition services with special focus on the under-served and the under-privileged segments of the population. There has been steep fall in mortality and in specific diseases such as polio, neonatal tetanus and other vaccine-preventable diseases; the incidence of leprosy too, has declined. The disease burden due to communicable, non-communicable diseases and nutritional problems, however, continues to be high in the country.

The last decade witnessed an improvement in literacy rates from 52% in 1991 to 65% in 2001 (Table 1.8). At the same time, there are many without access to education — out of approximately 200 million children in the age group 6-14 years, only 120 million are in schools and the net attendance in the primary level is only 66% of the enrolment (Planning Commission, 2001).

Table 1.8 Literacy rates (percent of population)

|

Year |

Total |

Female |

Male |

||||

|

Rural |

Urban |

Total |

Rural |

Urban |

Total |

||

|

1971 |

29.5 |

13.2 |

42.1 |

18.7 |

33.7 |

61.3 |

39.5 |

|

1981 |

43.7 |

21.8 |

56.4 |

29.9 |

49.7 |

76.8 |

56.5 |

|

1991 |

52.2 |

30.6 |

64.1 |

39.3 |

57.9 |

81.1 |

64.1 |

|

2001 |

65.4 |

46.70 |

73.20 |

54.16 |

71.40 |

86.70 |

75.85 |

Source.

MoF (2002)As the foregoing section indicates, there has been improvement in the various facets of human development; yet though there is still a long way to go. levels of achievement are still not adequate. That poverty goes beyond lack of adequate income, and should be viewed more as a state of deprivation spanning the social, economic, and political context of the people that prevents their equal participation in the development process, is now well appreciated. Recognising the need for this holistic view of welfare, the government has recently come out with a well-researched and contextually relevant approach to mapping the state of human development in the country in its many facets through a range of indicators that will be useful in formulating and monitoring public policy.

As the Human Development Report brings out, the HDI (human development indicator) for the country has improved significantly between 1980 and 2001, improving by nearly 26% in the eighties and another 24% in the nineties (Planning Commission, 2002). There has been an improvement both in rural as well as in urban areas. Further, though the rural-urban gap in the level of human development continues to be significant, it has declined during the period. Inequalities across states on the HDI are less than the income inequality as reflected in per capita State Domestic Product. The index of gender inequality measuring the attainments in human development indicators for females as a proportion of that of males has also improved, though marginally, in the 1980s. At the national level, the GEI increased from 62% in the early eighties to 67.6% in the early nineties. This implies that on an average, the attainments of women on human development indicators were only two-thirds of those of men. At the state level, those that have done well in improving female literacy are also the ones that have substantially improved their gender equality. On the whole, gender disparities across the states have declined over the period.

The HPI (human poverty index) conceptualised in terms of various aspects of deprivation, covering accessibility to minimum services, has considerably declined during the eighties, in line with the head count measure discussed earlier. However, there are considerable variations in terms of the rural -urban incidence as well as at the state level. The rural-urban ratio for the proportion of the HPI is nearly twice as high as that on the head count ratio of poverty, possibly reflecting the lower levels of basic amenities in rural areas. At the state level, while the HDI declined in all states, interstate differences have persisted.

Harnessing science and technology

Technology is a fundamental input into sustained growth and welfare. The role of science and technology in decoupling economic growth with environmental degradation has also become important. The promotion of science and technology for the cause of development has been one of the guiding principles of planned development in Independent India. There has been significant growth in capabilities and achievements in several areas, namely, space sciences, astronomy, meteorology, disaster warning, electronics, defence, nuclear, material and medicine. Industry interface, community involvement and international co-operation in development of science and technology have been strengthened over time. Increasingly the government has sought to support socially oriented S&T interventions for rural areas and weaker sections. The role of remote sensing satellite system for natural resource monitoring and management has also gained importance. Since 1990’s in particular, sustained efforts have been made for developing newly emerging areas such as information and communication services, biotechnology and new and renewable sources of sources.

The government recognizes the enormous potential of information and communication technology as a catalyst towards sustainable development through access to information thus facilitating market access, education, and participative and transparent governance. India enjoys a competitive advantage in software and related services in the form of abundant qualified manpower and expertise in state-of- the-art hardware and software platforms. The Department of Information Technology in the Government of India is guided by the vision of making India an IT super power by the year 2008. Independent estimates suggest that by 2008, the IT industry will be the single largest contributor to the GDP of the country and large employment generator.

In the area of biotechnology, the government strives for "attaining new heights in biotechnology research, shaping biotechnology into a premier precision tool of the future for creation of wealth and ensuring social justice - specially for the welfare of the poor". Significant advances have already been made in the growth and application of biotechnology in the broad areas of agriculture, health care, animal sciences, environment, and industry. Specifically, several initiatives have been taken to promote transgenic research in plants with emphasis on pest and disease resistance, nutritional quality, molecular biology of human genetic disorders, brain research, plant genome research, development validation and commercialisation of diagnostic kits and vaccines for communicable diseases, food biotechnology, biodiversity conservation and bioprospecting, setting up of micropropagation parks and biotechnology based development for weaker sections, rural areas and women.

Sustainable energy development is a key element of a sustainable growth outlook. India has made rapid advances in harnessing clean energy and boasts of one of the world's largest renewable energy programmes covering the whole spectrum of renewable energy technologies for a variety of grid and off grid applications. The country has the largest decentralised solar energy programme, the second largest biogas and improved cookstoves programme, and the fifth largest wind power programme in the world. A substantial manufacturing base has been created in a variety of new and renewable sources of energy, placing India not only in a position to export technologies but also to offer technical expertise to other countries. Renewable energy technologies are an important means of social development in the country, being an attractive, and sometimes only option to provide energy to non-electrified areas that are too remote for grid electrification.

Environmental sustainability

Environmental sustainability considerations have been an integral part of the Indian culture. The need for conservation and sustainable use of natural resources has been expressed in Indian scriptures more than three thousand years old and is reflected in our constitutional, legislative and policy framework as also international commitments. Apart from concerns about increasing air and water pollution, degradation of land and forests along with loss of biodiversity have also come into focus. Specific measures were initiated way back in 1972 after the Stockholm Declaration. Since then a full-fledged Ministry of Environment and Forests has evolved and an extensive legislative network now exists to address environmental issues. There have also been several policy initiatives to safeguard the environment. These are discussed in detail in later chapters.

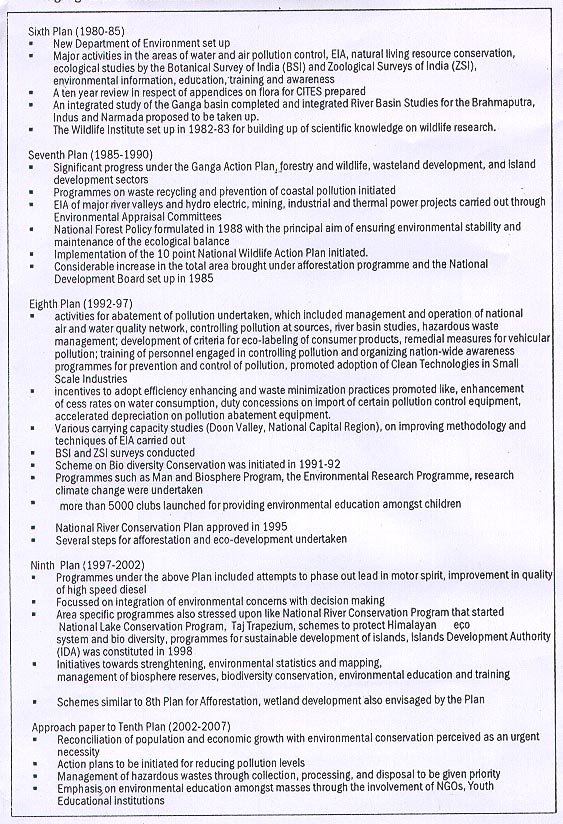

Sustainability concerns have become an intrinsic component of the planning process (Annexure 1.1). The Ninth Five-Year Plan (1997-2002) explicitly recognized the synergy between environment, health and development and identified as one of its core objectives the need for ensuring environmental sustainability of the development process through social mobilization and participation of people at all levels. Environmental awareness programmes supported by the government and NGOs have also gained momentum in recent times. The country has signed and ratified several international conventions and agreements on the environment and related issues and has been effectively implementing these. The efforts made so far need to be carried forward by strengthening the existing attempts at the domestic level and reinforcing international cooperation in dealing with issues related to social development and the environment.

Towards sustainable development

The Earth Summit 21 awakened countries to the need for integrating sustainable development concerns in the planning process. Agenda 21, adopted at the Summit put forward a road map directing this change, spanning a wide spectrum of social, economic and environmental issues from combating poverty and improving access to basic services to increasing the role of the private sector and international cooperation, to conservation and management of natural resources.

The principles underlying Agenda 21 objectives have been central to development planning in India. Since Independence, the country has paved the way towards social development through multi-faceted development planning, guided by the objectives of poverty eradication and provision of basic needs.

The governance structure of the country is founded on the principles of democracy, equality and the rule of law. The basic democratic character of the Indian State has, since Independence, become stronger, wider and deeper, even as the structure has itself evolved to accommodate new challenges. In order to strengthen the basic character of democracy i.e. the flow of power upward from the people- there has been emphasis on strengthening local self-governance in villages and urban areas alike. Education, awareness, a vibrant print and electronic media and the rapid spread of information technology have led to an ever-widening participation of the civil society in the development process of the country.

The government has, over the years, developed a number of programmes that aim at eradicating poverty either through directly targeted programmes such as employment generation, training and building-up assets of the poor or indirectly through human development with an emphasis on health, education, and minimum needs including protection of human rights and raising the social status of the weak and the poor. As a result of these initiatives the percentage of population under poverty has continuously declined. Population growth has decelerated below 2% for the first time in four decades and literacy has increased from 52% in 1991 to 65% in 2001, the performance being even more impressive in some states.

The government recognizes the role of economic growth in improving the quality of life of the people. Growth enables expansion of productive employment and provides the necessary financial and technological resources for development programmes. As discussed earlier, since 1991, the country has initiated economic reforms including trade, financial and structural reforms allowing the private sector into hitherto restricted areas. These measures have ushered in a new age of productivity and competitiveness. GDP growth in the post-reforms period has accelerated from an average of about 5.7% in the 1980s to an average of about 6.5% in the Eighth and Ninth Plan periods, making India one of the ten fastest-growing developing economies.

Environmental considerations have been an integral part of the Indian culture and have increasingly integrated in the planning process. This is reflected in our constitutional, legislative and policy framework as also international commitments.

The government recognizes that these laudable objectives are clouded by concerns. The economy is currently in a decelerating phase, which is compounded by the general slow-down in the world economy. On the social front, too, there remains much to be done. Despite the significant progress in areas of poverty eradication, literacy and health standards, there still remains a gulf between the standards prevailing in India and the rest of the world. According to the Human Development Report (HDR) 2001, India ranks 115th in the world as judged by the Human Development Indicator, an index incorporating various measures of GNP, longevity, health, nutritional standards, literacy, water supply and the like. India's HDI was estimated at 52.9 compared to the average of 64.5 for all developing countries. Growth in the 1990s has generated less employment than was expected. The infant mortality rate has stagnated at 72 per 1000 for the last several years. There remain perceptible rural-urban and regional differences in access to basic services. Per capita electricity consumption in the country is only one-sixth the world average and one-twentieth that in high-income countries and, as many as 60% of rural households and 20% of urban households do not have an electricity connection (Planning Commission, 2001). Land and forest degradation in rural areas and over-exploitation of groundwater is seriously threatening the sustainability of food production and pollution in cities is on the rise.

The Government of India is cognisant of these challenges as the country sets out to prepare the first development plan of this millennium. While seeking to achieve a high and sustained economic growth, it realizes that economic growth standing on an unsteady social and environmental foundation cannot be sustained. The Tenth Five-Year Plan assigns primacy to enhancement of human well-being which includes not only adequate level of food consumption and other consumer goods but also access to basic social services especially education, health, drinking water and basic sanitation. It also assigns primacy to the expansion of economic and social opportunities for all individuals and groups and wider participation in decision-making. Conservation and management of natural resources is an important focus of the plan.

As a nation that has been actively associated with the global pursuit of sustainable development, India's commitment to Agenda 21 re-emphasises the principles that have long guided development planning in the country. In order that the country build upon the gains of the past and address the weaknesses that have persisted within it, it is necessary that the international community, especially the developed world, recommit itself to the global partnership forged at Rio. This partnership was based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibility as the developed world acknowledged the burden their societies had placed on the global environment and the distinct advantage they commanded with respect to technologies and financial resources. The commitments made by the developed world towards enhanced and stable concessional financing to the developing world have largely gone unfulfilled. As developing countries struggle with their limited financial resources to meet the immediate and more basic requirements of their people, it is imperative that the North plays its role in order to operationlize the long term mandate of

Agenda 21.

Structure of the report

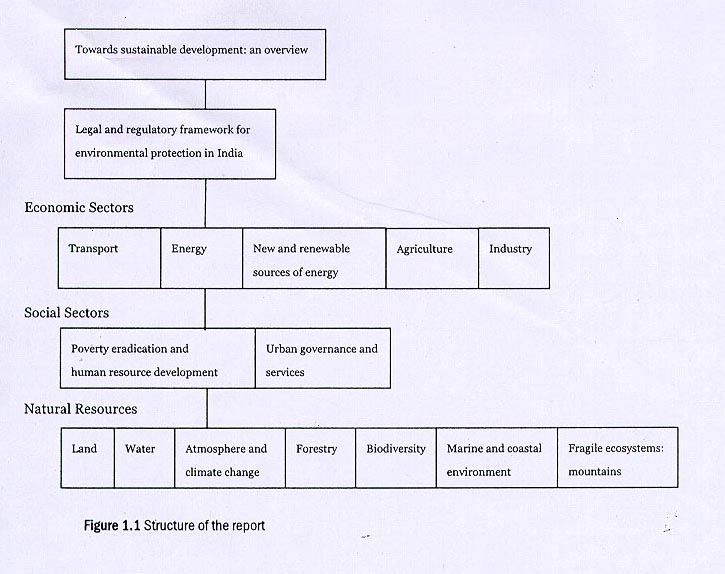

This study undertakes a sectoral analysis of achievements and concerns in the backdrop of Agenda 21 objectives with the aim of evolving directions and strategies for sustainable development at the sectoral level. The scope and structure of the report are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

The analysis for each sector (in the case of economic and social sectors and natural resources) begins with a brief overview of the sector followed by a discussion of Agenda 21 concerns relevant to the sector in the Indian context. Major policy and other development are highlighted and analyzed to bring out achievements and concerns vis-à-vis the objectives set out in Agenda 21. Each chapter concludes with directions and strategies for sustainable development.

Highlights of environmental initiatives in Five_year Plans

References

Accessed on 28.9.2001

Accessed on 28.9.2001

Accessed on 10.10.2001

BP Statistical Review of the World Energy (June 2001)

http://www.bp.com

Accessed on 17.10.2001

Population and water resources of India

In The Inevitable Billion Plus: science, population and development, edited by V Gowarikar

Pune: Unmesh Communications. 452 pp.

Sustaining water: population and the future of renewable water supplies

Washington, DC: Population and Environmental Program, Population Action International. 56 pp.

The State of Forests Report 1999

Dehra Dun: Forest Survey of India

Economic Survey 2000-2001

New Delhi: Economic Division, Ministry of Finance.

Economic Survey 2001-2002

New Delhi: Economic Division, Ministry of Finance.

Government of India

http://mohfw.nic.in

Annual Report 1999-2000

New Delhi: Ministry of Rural Development. 211 pp.

NSS 55th Round July 1999-June 2000

New Delhi: National Sample Survey Organisation, Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation.

Approach Paper to the Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-07)

New Delhi: Planning Commission. 49 pp.

Indian Agriculture Emerging Perspectives and Policy Issues

As produced in Indian Economy since Independence ed. Uma Kapila 1998-99 edition;

pp. 296-325

India human development report, a profile of Indian states in the 1990s

National Council of Applied Economic Research, Oxford University Press. 370 pp.

TEDDY 2001/2002 (TERI Energy Data, Directory, and Yearbook)

New Delhi: Tata Energy Research Institute. pp. 454

DISHA (Directions, innovations, and strategies for harnessing action)

New Delhi: Tata Energy Research Institute. 368 pp.

Vol. 2: pp. 167-185, 228-258

New Delhi: Planning Commission. 463 pp.

New Delhi: Planning Commission.

Vol. 2: Sectoral Programmes of Development

New Delhi: Planning Commission. 480 pp.

Vol. 2: Thematic Issues and Sectoral Programmes

New Delhi: Planning Commission. 1059 pp.

Notes:

[1] In addition to Agenda 21, the assembled leaders signed the Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity; and endorsed the Rio Declaration and the Forest Principles.

[2] Q: quick estimates.

[3] Per capita net national product and GDP for 2000-01 are quick estimates by the GoI Economic Survey 2001/02.

[4] SRS-Sample Registration System.

[5] http://mohfw.nic.in.

[6] Head Count Ratio represents the percentage of population that earns/spends below a certain level of income. This level is identified as the poverty line. Poverty line (monthly per capita) for the rural India is Rs 205.84 (93-94), for urban India is Rs 281.35 (93-94); Planning Commission.