Introduction

The atmosphere is a common global resource, adversely affected by the by-products of anthropogenic activity. Its preservation is imperative for present and future generations. Agenda 21 proposes directions to achieve the dual objectives of economic progress and atmospheric protection.

This chapter studies policies which have an impact on atmospheric quality to examine the extent to which Agenda 21 concerns for the protection of the atmosphere have been addressed. The chapter begins with an assessment of the pressures on the global atmosphere, followed by a discussion of Agenda 21 concerns for its protection. The institutional set-up and legislative framework for addressing global atmospheric problems is examined next. Finally, a review and analysis of the existing policies for atmospheric protection is undertaken to study the convergence with Agenda 21.

This chapter focuses on the global atmospheric problems of climate change and ozone depletion. It must be noted that India is a developing country with a very small contribution to greenhouse gas concentration, and does not have emission reduction commitments at present. However, initiatives that address immediate national and developmental priorities will contribute significantly to the global effort towards atmospheric protection. Local air quality issues are dealt with in chapters on energy, transport, and industry.

Overview

Greenhouse gases

There is worldwide concerns about rising emissions of greenhouse gases from human activities such as power generation, industrialization, and deforestation. The main naturally occurring greenhouse gases are CO2, CH4, and N2O, which trap radiation emitted by the earth, leading to higher temperatures, changed precipitation patterns, and rises in sea level.

The Third Assessment Report, 2001 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that global average temperatures could rise by 1.4-5.8° C over the period 1990-2100. This would have wide-ranging impacts including a decline in crop yields, inundation of land in coastal areas, increased frequency and intensity of extreme events, spread of vector-borne diseases, etc.

Climate change is primarily determined by the total stock of GHGs in the atmosphere and not by annual GHG emissions. Developed countries have been responsible for more than 60% of the total global stock of GHGs (Figure 8.1).

In 1990, total CO2-equivalent

[1] emissions from India were 1 001 352 Gg, which was approximately 3% of global emissions (Table 8.1).Table 8.1 India’s national greenhouse gas inventory for 1990 (in Gg)

|

GHG sources and sinks |

CO2 emissions |

CO2 removals |

CH4 |

N2O |

NOx |

CO |

CO2-equivalent (CO2+CH4+N2O)[2] |

|

I. Energy |

|||||||

|

Fuel combustion |

508600 |

||||||

|

Energy and transformation industries |

2684 [3] |

3493 [3] |

508600 |

||||

|

Biomass burning |

300460 [4] |

1579 |

11 |

400 |

11472 |

36569 |

|

|

B. Fugitive emissions from fuels |

|||||||

|

Solid fuels |

330 |

6930 |

|||||

|

Oil and natural gas |

626 |

13146 |

|||||

|

Total emissions from energy sector (fuel combustion + fugitive emissions) |

508600 |

2535 |

11 |

3084 |

14965 |

565245 |

|

|

II. Industrial processes |

24200 |

1 |

24510 |

||||

|

III. Solvents and other products |

|||||||

|

IV. Agriculture |

|||||||

|

Enteric fermentation |

7563 |

158823 |

|||||

|

Manure management |

905 |

19005 |

|||||

|

Rice cultivation |

4070 [5] |

85470 |

|||||

|

Agricultural soils |

240 |

74400 |

|||||

|

Prescribed burning of savannas |

|||||||

|

Field burning of agricultural residues |

116 |

3 |

109 |

3038 |

3366 |

||

|

Total emissions from agricultural sources |

12654 |

243 |

109 |

3038 |

341064 |

||

|

V. Land-use change and forestry |

|||||||

|

Change in forests and other woody biomass stock |

-6171 |

-6171 |

|||||

|

Forests and grassland conversion |

52385 |

52385 |

|||||

|

Abandonment of managed lands |

-44729 |

-44729 |

|||||

|

Total emissions from land-use change and forestry sector |

52385 |

-50900 |

1485 |

||||

|

VI. Waste |

|||||||

|

Solid waste disposal on land |

334 |

7014 |

|||||

|

Domestic and commercial waste water |

49 |

1029 |

|||||

|

Industrial waste water |

2905 |

61005 |

|||||

|

Other waste |

|||||||

|

Total emissions from waste |

3288 |

69048 |

|||||

|

Total national emissions and removals |

585185 |

-50900 |

18477 |

255 |

3193 |

18003 |

1001352 |

Source. ADB-GEF-UNDP (1998)

In 1990, in per capita terms, India emitted 1.19 tonnes of CO2-equivalent, compared with 8.8 tonnes by Japan, and 19.8 tonnes by the United States. The energy sector was the largest emitter of CO2 contributing to 55% of national emissions. These also include emissions from road transport, coal mining, and fugitive emissions from oil and natural gas. Agriculture is the second largest source of GHGs in India; methane emissions from enteric fermentation in domestic animals, manure management, rice cultivation, and burning of agricultural residues constitute 34% of national GHG emissions. The net uptake and emissions from the land use change and forestry sector were almost equal, resulting in negligible emissions (ADB-GEF-UNDP, 1998).

Table 8.2 shows the change in CO2 equivalent emissions from fuel combustion over the period 1990-99 in India and other countries.

Table 8.2 CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion

|

Total million tonnes CO2 |

||

|

1990 |

1999 |

|

|

World |

21279.4 (100) |

23172.2 (100) |

|

USA |

4845.9 (23) |

5584.8 (24) |

|

EU |

3133.7 (15) |

3106.1 (13) |

|

Japan |

1048.5 (5) |

1158.5 (5) |

|

India |

591.12 (3) |

903.82 (4) |

|

China |

2428.9(11) |

3051.11(13) |

|

Brazil |

201.01 (1) |

305.55 (1) |

Note: Figures in brackets denote % of world total

Source. IEA ( 2001)

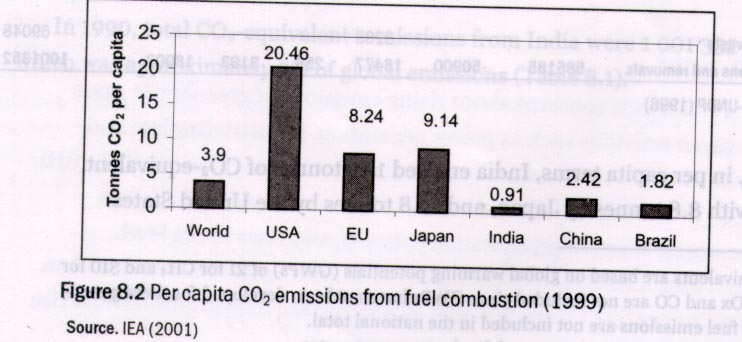

Figure 8.2 shows that in 1999 per capita emissions from fuel combustion from India were much lower than for the US, EU and Japan, and one-fourth of the world average.

Ozone-depleting substances

The ozone layer in the stratosphere is at risk from compounds containing different combinations of chlorine, fluorine, bromine, carbon, and hydrogen. These compounds (e.g. chlorofluorocarbons, hydrofluorocarbons, carbon tetrachloride, etc.) are collectively known as ozone-depleting substances (ODS) and are used in refrigeration, aerosol propellants such as body sprays, foam-blowing, and industrial solvents. They react with and deplete stratospheric ozone, allowing harmful UV radiation to reach the earth. This increased radiation can change genetic structure, affect immune systems, inhibit plant growth, and increase the incidence of eye cataract and skin cancer.

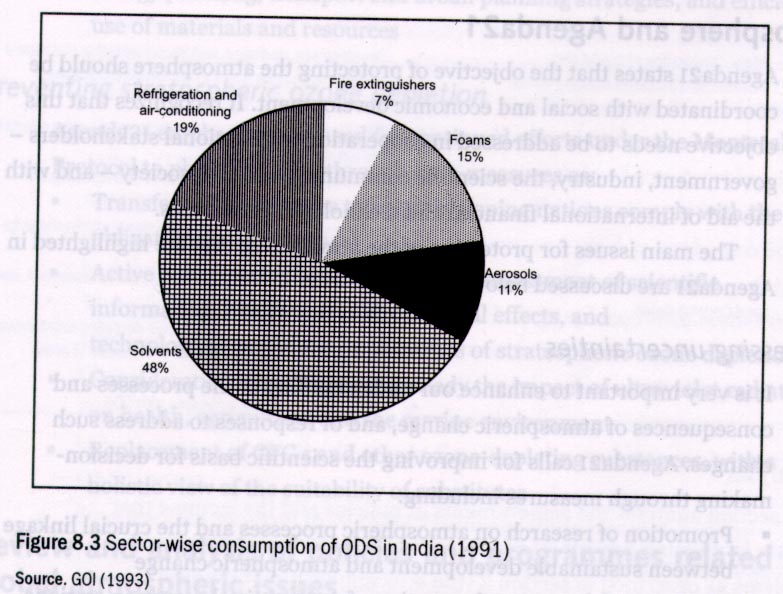

In 1991, India's consumption of ODS was 10370 tonnes; of this, about 85% was produced domestically and 15% was imported. India’s consumption amounted to about 1.2% of the global consumption of ODS, and less than 10g in per capita terms. The industry-wise consumption of ODS in 1991 is shown in Figure 8.3. Table 8.3 compares the change in consumption over the period 1991-1999, by type of ODS.

Table 8.3 ODS consumption in India

|

Name of ODS |

Quantity in 1991 (metric tonnes) |

Quantity in 1999 (metric tonnes) |

|

CFC-11 CFC-12 CFC-13 Halon-1211 Halon-1301 Carbon tetrachloride Methyl chloroform Methyl bromide HCFC-22 |

1898 2852 321.5 550 197 4003 550 - - |

6167 2050 - 106 47 14635 1415 [6] 6.64 8000 [7] |

Source. UNEP-CUTS-SAWTEE (2001)

Atmosphere and Agenda21

Agenda21 states that the objective of protecting the atmosphere should be coordinated with social and economic development. It recognizes that this objective needs to be addressed in cooperation with national stakeholders – government, industry, the scientific community, and civil society – and with the aid of international financial and technological resources.

The main issues for protection of the atmosphere that are highlighted in Agenda21 are discussed below.

Addressing uncertainties

It is very important to enhance our understanding of the processes and consequences of atmospheric change, and of responses to address such changes. Agenda21 calls for improving the scientific basis for decision-making through measures including:

Promoting sustainable development

Integrating economic growth with atmospheric protection requires policies and programmes that promote greater efficiency in energy production and consumption, environmentally sound transportation and industrial development. The directions for future development are:

Preventing stratospheric ozone depletion

Agenda21 emphasizes the need for continued efforts under the Montreal Protocol to phase out ODS through such measures as:

Review and analysis of policies and programmes related to global atmospheric issues

Highlights of legislation, policies and programmes

Relevant policies and legislation related to global atmospheric issues are briefly reviewed in Table 8.4.

Table 8.4 Review of polices and legislation in India governing global atmospheric issues

|

Year |

Policies/ legislation |

Salient features |

|

1991 |

Vienna Convention for the protection of the ozone layer |

India became a party in June 1991 |

|

1992 |

Montreal Protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer |

|

|

1992 |

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

|

|

1997 |

Male¢ Declaration of the SAARC Environment Ministers Meeting on the Environment Action Plan |

|

|

2000 |

Ozone Depleting Substances (Regulation and Control) Rules |

|

Policy analysis

This section analyses the achievements of policies and the lacunae that remain in meeting Agenda 21 concerns regarding global atmospheric problems as described in section 3 (the atmosphere and Agenda21) above.

India has a detailed institutional and legislative framework for pollution abatement. Apart from policies, legislation and programmes there is also a strong institutional structure designed for the protection of the atmosphere. All these reflect an intention to integrate environmental considerations into decision-making at every level, with an emphasis on preventing pollution. It also brings to the fore, the government’s strong intention to encourage increased interaction, move away from a strictly regulatory framework, and create an enabling environment for the adoption of cleaner technologies. This is further emphasized by the Ninth Plan statement that India’s strategies for environmental protection are guided by Agenda21 principles.

Addressing uncertainties

Agenda 21 highlights the need to improve scientific understanding about processes that impact our atmosphere. Given its tropical location and its significant dependence on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture and forestry, India is vulnerable to climate change. It is, therefore, important to develop a better understanding of climate processes in the Indian subcontinent, assess potential socio-economic impacts, and build the capacity to adapt to climate change.

Current initiatives in this section include:

There is need for detailed information about sectoral GHG emissions, country-specific emission factors, and monitoring methods. Further work in these areas is being undertaken as part of the preparation of the country’s first National Communication to the UNFCCC. The greenhouse gas inventory for the country is being prepared for the base year 1994, and will cover five sectors: energy, industrial processes, agriculture, forestry, and waste. Vulnerability and adaptation assessment is also part of the National Communication project.

Promotion of sustainable development

The energy sector is the main source of greenhouse gases (Table 8.1). India is pursuing energy conservation, promotion of cleaner fuels, renewable energy technologies. The Energy Conservation Act is a noteworthy initiative in this regard. Other significant initiatives include the unbundling and privatization of the electricity sector, introduction of Bharat I and II norms in the transport sector [8], etc. Other significant measures in the transport sector include conversion of two- to four-stroke engines in two-wheelers, and demonstration of the use of electric- and battery-operated vehicles.

The Government of India has been consistently promoting power generation from renewable sources. Today, India has one of the largest renewable energy programmes in the world, and is the world’s fifth-largest producer of wind energy, with an installed capacity of 1507 MW. The government offers several fiscal and financial incentives to encourage the adoption of such technologies as bagasse-based cogeneration, biomass consumption, grid connected solar photo-voltaic (PV) application, wind battery chargers, wind pumps etc. These are described in the chapter on Renewables.

The Technology Information, Forecasting and Assessment Council established under the Department of Science and Technology facilitates the transfer of environmentally sound technology. It has conducted a study on clean coal technologies, which are critically important given the large share (nearly 70%) of coal-based power generation in India, and the high ash content of the Indian coal.

In addition to these measures, India also pursues policies promoting afforestation and wasteland development. Under the UNFCCC, developing countries such as India do not have GHG mitigation commitments in recognition of their small contribution to the greenhouse problem as well as low financial and technical capacities. The Ministry of Environment and Forests is the nodal agency for climate change issues in India. It has constituted a Working Group on the UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol to deliberate upon issues emerging from the climate change negotiations. It has also established a task group on Activities Implemented Jointly (AIJ) to consider and recommend bilateral and multilateral projects aimed at GHG reduction. India is also going to host the eighth session of the Conference of Parties (COP-8) to the UNFCC during October 23-November 1, 2002.

The Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC was adopted in 1997 and requires developed countries listed in Annex B of the Protocol to reduce their GHG emissions to 5.2% below 1990 levels on average. Under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) introduced in the Protocol, developing countries such as India can participate in joint GHG mitigation projects. India has not yet signed the Protocol. The Government of India has, however, indicated its support of the CDM in a decision made prior to the sixth Conference of Parties to the UNFCCC (COP-6) in 2000. Priority projects are being identified for CDM investment in sectors such as power generation and renewable energy. At the resumed session of the seventh Conference of Parties (COP-7), it was agreed to adopt fast-track procedures for the approval of small-scale CDM projects in renewable energy and energy efficiency, which also matches India’s interests.

The country’s experience with Activities Implemented Jointly (AIJ), (Table 8.5) and Global Environment Facility (GEF) projects is also valuable in this regard.

Table 8.5 Pilot phase AIJ projects underway in India (as of December 2001)

|

Project |

Location |

Investor |

Host |

|

Integrated agricultural demand-side management |

Andhra Pradesh |

World Bank/Norway |

Andhra Pradesh State Electricity Board |

|

DESI power: biomass gasification |

20 sites |

The Netherlands |

DESI Power, Development Alternatives |

|

Hybrid Renewable Energy Project |

Rajasthan |

Australia |

Brahmakumaris Academy for a better world |

Source. TERI (2001)

India has GEF projects in the following areas.

COP-7 also agreed upon increased replenishment of GEF, the establishment of an adaptation fund, and a special climate change fund. This last fund will finance activities that are complementary to those funded by the GEF, including:

Despite the above initiatives, India requires substantial new and additional resources to implement a less-polluting and carbon-intensive path. In the long run, stabilization of GHG emissions requires the convergence of per capita emissions from developed and developing countries towards a common range. Adequate institutional capacity-building is critical to meeting the requirements of mitigation, adaptation, and CDM operationalization.

Preventing stratospheric ozone depletion

India acceded to the Montreal Protocol along with its London Amendment on 19 June 1992. The India Programme for the phase-out of ODS under the Montreal Protocol was approved in November 1993. The MoEF has established the Ozone Cell and the Steering Committee on the Montreal Protocol to facilitate implementation of the objectives of the India Country Programme. India’s efforts to protect the ozone layer are guided by the need to minimize economic dislocation, encourage indigenous production of substitutes, and address the special requirements of small and medium enterprises.

To meet India’s commitments under the Montreal Protocol, the Government of India has also taken some major policy decisions.

Strategies for sustainable development

Agenda21 brings to the fore key concerns for the preservation of the atmosphere – both, regarding global problems such as climate change and stratospheric ozone depletion, and the pressing issues of local air quality, a priority for developing countries. By exploiting the synergies that exist between local and global environmental priorities, India can optimize the use of international resources for national development.

There exists a detailed policy framework in India to address these concerns, with appropriate legislation being formulated in the pre-Rio as well as post-Rio periods. The Approach Paper to Tenth Five-Year Plan, like its predecessor, recognizes the need for a cleaner atmosphere and states that efforts should be made to reduce air pollution in each of the sectors that creates pressures on the atmosphere.

The challenge, however, is to improve the enforcement of these policies by institutional strengthening and capacity-building, improved monitoring and reporting systems, and adoption of appropriate market-based instruments. International cooperation should be promoted for the transfer of financial resources and cleaner technologies. In keeping with the suggestion of CSD-IX, attempts will be made to explore ways of increasing financial resources and create innovative financing solutions also by debt relief. Where possible, efforts should be made to facilitate foreign investment, reverse the downward trend in ODA, and fulfil the commitments undertaken to reach the accepted United Nations target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product (GNP) as soon as possible.

References

Agenda 21, United Nations

http://www.un.org/esa/sustdevADB-GEF-UNDP. 1998

Asia least-cost greenhouse gas abatement strategy: India

Manila: Asian Development Bank

GoI. 1993

India: sustaining development

New Delhi: Government of India

IEA. 2001

CO2 emissions from fuel combustion 1971-1999

Paris: International Energy Agency

IMD. 2001

www.imd.ernet.inAccessed on 8 November 2001

MoEF. 1993

Country programme: phase-out of ozone-depleting substances under the Montreal Protocol

New Delhi: Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India.

Ninth Five-Year Plan: 1997-2002

Vol. 2: Thematic Issues and Sectoral Programmes

New Delhi: Planning Commission. 1059 pp.

Planning Commission. 2001

Approach Paper to the Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-07)

New Delhi: Government of India, Planning Commission. 49 pp.

TERI.2001

Survey on potential of model projects for increasing the efficiency use of energy in India

Prepared for New Energy Industrial Technology Development Organization, Bangkok

New Delhi: Tata Energy Research Institute

UNEP-CUTS-SAWTEE. 2001

South Asian consultation on atmospheric issues

WRI. 2001

The U.S., developing countries, and climate protection: leadership or stalemate?

Washington, DC: World Resources Institute

Notes:

[1] This takes into consideration the fact that greenhouse gases have different global warming potentials.

[2] CO2-equivalents are based on global warming potentials (GWPs) of 21 for CH4 and 310 for N2O. NOx and CO are not included since GWPs have not been developed for these gases. Bunker fuel emissions are not included in the national total.

[3] NOx and CO emissions are computed for the transport sector.

[4] CO2 emissions from biomass burning are not included in the national totals.

[5] CH4 emissions according to IPCC 1996 methodology.

[6] 1996 data

[7] 1998 data

[8] Bharat I norms have been implemented from April 1st 2000. These are applicable to the two- and three-wheeler segment and are stricter than Euro II norms. Bharat II norms will be applicable from April, 2005.